If You Didn’t Like That Christian Ministry’s Anti-‘Captain Marvel’ Article, Read This

Some of you may have read a Christian ministry’s web article that took the movie Captain Marvel to task for (supposed) feminism.1

My friend Cap Stewart kindly yet firmly took the article to task here. Among other issues, he challenged the original article’s lack of simple genre comprehension. The author seems to have lacked some basic familiarity with superhero story “rules” and intentions:

Inexplicably, Morse [the original article author] is conflating the fairy tale fantasy and superhero genres. Captain Marvel is not a Disney princess, nor is she trying to be. Her physical abilities are way above and beyond anything a princess—or any woman—could ever do, just as the physical abilities of Captain America are far beyond anything a prince—or a man—could ever do.

When talking about the abandonment of the “traditional princess vibe” (as if that were the standard by which superhero movies should be judged), it’s interesting that Morse uses Cinderella and Belle as examples. Disney has recently produced live action versions of both those stories, actually, and in neither of these modern retellings does the princess swap her traditional accoutrements for combat paraphernalia. Morse’s argument here makes no logical sense.

The goal of a superhero movie is not to get people to try flying off balconies or become autonomous vigilantes. No, the goal of the superhero genre is not audience imitation but rather audience inspiration. The virtues and character arcs of superheroes can—and do—motivate us to pursue virtue and character growth ourselves.2

I might suggest the article’s writer also stumbled into a larger pitfall.

Mind you, I want to be fair, and I have not read the author’s entire body of work on subjects relating to popular culture.

At the same time, I generally find this true:

- Christian tries to engage a story or song from human popular culture.

- Christian gets criticism (harsh or rational), because he hasn’t shown basic familiarity with the story’s genre or intent.

- Very likely, the Christian has not biblically worked out the purpose of human popular culture in the first place.

I try to go over this in the article Christians, Please Stop Warning Against Human Popular Culture Until You Know What It’s For:

Entertainment is never “just entertainment.” The apostle Paul says to take every thought captive, and this must include thoughts relating to the stories and human creations we enjoy.

But the Christian leader who challenges popular culture “consumption” needs to say more than, “Popular culture is harmless, but you should love Jesus more than entertainment.”

He needs to show how loving Jesus transforms our view of entertainment—or rather, stories, songs, games, and beyond.

He needs to allow for the fact that some Christians are not passive about these popular works; in fact, we can be very proactive and thoughtful about human stories and songs (in biblical ways or otherwise!).

Christian leaders need to stop using words like “consume.” This makes us imagine some unthinking, careless gorging of one’s self, all alone in a dark living room, complete with fake-cheese snacks and a flickering TV screen. Why not instead try words like “engage,” “take captive,” “redeem,” or even “avoid based on personal scruples” about any particular story/song/game?

He may also try the word recreation—a far more biblical framing than “entertainment.”

Why not frame this topic in a biblical worldview, rather than use the world’s language?

Why not discuss popular culture—human stories and songs—in terms of human creativity being a gift from God? The way some pastors talk, popular culture is some alien (even if “harmless”) thing unrelated to God. But if God gives this gift (of popular culture-creation), then He, not us, defines the terms of how the gift is best used—to glorify Him, to guard against idolatry, and to make sure we get the most joy out of using the gift in the ways He has prescribed.

Why not explore how Jesus has built the work-rest rhythm into the universe, starting right in Genesis 1? Why not consider how stories and songs are part of being human, whether they’re shared around a campfire or enacted on your tablet screen? Why not allow the possibility that Scripture seems to allow—that we will create cultural works in eternity?

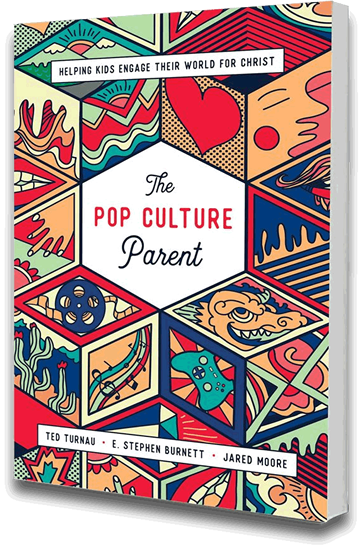

I would even go so far as to suggest that if the Christian leader cannot allude to the biblical view of recreation, or articulate this view in his body of work somewhere, he probably ought not talk about culture or popular culture at all.

No, I don’t mean that every Christian ought to become as I am, reviewing novels, movies, and anime, and often hanging out with Christian folks who like doing the same.

But Christian leader, pastor, or teacher: if you can’t show that you know what popular culture is for in the first place, using biblical anthropology, I honestly struggle to listen seriously when you only warn against popular culture.3

- Rumors of Captain Marvel‘s supposed radical feminism have been grossly exaggerated. If anything, adding even some preachy feminism could have given the story more substance and direction. ↩

- Cap Stewart, “Captain Marvel, Disney Princesses, and the ‘Feminist Agenda,’” CapStewart.com, March 15, 2019. ↩

- E. Stephen Burnett, “Christians, Please Stop Warning Against Popular Culture Until You Know What It’s For,” Speculative Faith, Nov. 6, 2017. See also “When Pastors Criticize Popular Culture,” Speculative Faith, Aug. 24, 2017. ↩

My friend, while I agree Christians really should understand genre conventions before lanching into sharp criticism of an exemplar of a genre, I feel an objection rather against my will rising verses your approach to this topic.

The idea that stories are a part of culture and creating culture is a Biblical mandate in and of itself fails to account for the villian here (something a superhero story, ironically, would not fail to do). Who is Satan! Why no, the Evil One is not a figment of a Pentecostal’s or Fundamentalist’s imagination (nor mine). He is far more real than Thanos and he really, no kidding, tries to corrupt what is good in humanity and human arts.

That means an artistic creation cannot be presumed to be good simply because someone created it and its part of human culture. In fact, those considerations prove to be nearly (not totally but very close to) meaningless.

A Christian has a legitimate right to ask if a story reflects genuine truth, beauty, and goodness. If a story glorifies evil instead of condemning it. To include wondering if gender is well-represented in fiction.

Please don’t mistake my comment as a defense of the Christian writer you referenced. I haven’t read his piece. And I doubt I will.

My point is pointed directly at your thought process, my friend. Ok, stories are part of culture and making culture is good. Cool–but that has no bearing on whether or not a particular story has been corrupted, our good salad from the Garden of God dressed with arsenic paste.

Don’t through out true discernment with the bathwater of judging a story for reasons that make no sense. Please.

I’m in full agreement with your caution there, especially because I’ve seen plenty of Christian thinkers who believe they need only say “popular culture was originally good!” One must get to saying “there is plenty of bad” eventually. My point is that emphasizing only the bad, or presuming the bad, puts the cart before the horse. Just as we first talk about humans’ goodness, and then fallenness, and then creation’s goodness, and then fallenness, so we talk about human culture (in creation’s) goodness, and then fallenness. But even the fallenness is permeated with what theologians call “common grace,” God’s preserving influence so that we’re not nearly as terrible as we could be, and have no excuse to say we didn’t see anything in our lives that helped us to understand the self-revealing goodness of God.

Although, I would tend to emphasize the fact that humans corrupt things (thanks in part to Satan’s involvement in Gen. 3) before I start talking about Satan’s intentional corruption. Satan’s greatest achievement is setting off humanity on its own self-worshiping project.

I don’t know if it’s about what he thinks genre is for, or just what he thinks women are for, which seems to be that we’re set dressing for the fantasies he has about himself.