Secular YA May Fade, But Fantastic Christian Fiction Will Live On

I’ll risk this prediction: Within one generation, print fantasy novels1 will be Christian fiction’s default genre.

As opposed to, say, the modern assumption that “family fiction,” or “inspirational” fare, is Christianity’s default genre.

I’ve written about this a lot, and needn’t rehash all the reasons here. But two more reasons just entered my news feed.

First, why did I specify print fantasy?

Because, as Michael Kozlowski at GoodEReader.com notes, “Our love affair with ebooks is over.”2

Independent bookstores are the places where you drop in for the latest paperback, listen to a reading from a favorite author or find a unique gift for a unique friend. And they’re thriving. According to the American Booksellers Association, its membership grew for the ninth year in a row in 2018, with stores operating in more than 2,400 locations. Not only that, sales at independent bookstores are up 5% over 2017.

Meanwhile, sales for ebooks are completely stagnant. Ebook sales have slipped by 3.6% in 2018 and generated over $1 billion dollars. This is a far cry from 2015 when the format made over $2.84 billion dollars. Meanwhile hardback and paperback book sales grew by 6.2 percent and 2.2 percent, respectively.

In one generation, some enterprising businessperson will get a loan, and church support. She or he will open a new kind of Christian bookstore. Maybe it’ll be a little bit “hipster.” It may be a bit strange. It will have definite (and kinda happily cliche) Lewis/Tolkien references. They’ll probably host Bible studies and serve expensive coffee. And it will take off like a privately financed space rocket.

Would this owner embrace (rather than fear) the inevitable “underground” culture that Christians will no doubt inhabit in one generation? If so, even better. Behold your indie-run Christian speakeasy! Here you can read fantastic stories and debate theology. Maybe you can even poke godly fun at the ruling sexual-revolutionaries.

Second, why did I specify Christian fiction?

I think the Christian label will change definitions, because I think Christian fiction, by Christians, by name, has a great chance of escaping the “it’s bad” and “it’s restricted by rules” assumptions people have long believed about it.

By contrast, if we still believe the notion that only Christian fiction is full of can’t-say-this, can’t-say-that rules, we’re out of date.

In fact, it’s the religious devotees of Progressivism who are putting together legalistic rules. Some of these are so strict and so bad that they may make your (mythical) no-cussing, no-dancing, KJV-Only great-grandpa look like a bar-hopping louse.

We’re seeing this more frequently reported. I last wrote about this after the sad Amelie Wen Zhao situation. More recently, I caught this New York Times column from Jennifer Senior: “Teen Fiction and the Perils of Cancel Culture.” But it’s this newsletter, from YA writer Jesse Singal, that best collects the raw and anonymous examples from the worst of these new religious thought police.

Those writers who reached out from secure positions within YA or other genres were adamant that they not be named, that they sensed a real threat to their careers in the possibility of getting sucked into one of these outrage-vortexes — even by simply criticizing YA Twitter publicly. . . .

This came in from a published YA fantasy author:

I’m sending you this because I believe the community needs to change. It’s destroying itself. What started out as, in my opinion, an important effort to diversify books for children has become embroiled in far too much public grandstanding and private backstabbing. Debut authors — the targets of a majority of the latest call outs — do not have the industry or social clout within the community to push back or, really, to even recover career-wise from cancelling their books. It’s even more difficult when they are marginalized people themselves.

People in the YA community obsess over “receipts.” They keep screenshots of conversations just in case they ever need to publicly destroy someone. Carefully cultivated public personas are common. If secrets are a form of currency, then coming off as a friendly person is intended to get people to open up to you. It is an industry where a lot of people have “allies” instead of “friends” and they are perfectly willing to throw those people under the bus in order to maintain social clout within the community. The people who do value friendships are the quiet ones. We’re not here to grandstand. We’re here to write books.

But what you see on YA Twitter is, really, just what they’re willing to put out in public. The private stuff is very personal and it cuts very deeply. In this industry, you have to be careful who you open up to, because you never know when the details of your life are going to become gossip fodder.

If any Christian fan thinks his/her next favorite story could never come from Christian publishers, and so they should just strike off into the secular fantasy fields—well, I’m afraid they will need to contend with the gruesome foe of Progressivism and/or YA Twitter.

Perhaps it’s not impossible to conquer. Example: a fan or author could start by simply staying off YA Twitter and refusing to play this game.

God bless and Godspeed to the many faithful fans and creatives who are called into the secular-fantasy mission fields.

But, for those so called, why not also try joining the inevitable fantastic reboot of Christian-fiction-by-name?

Christian fiction’s fantasy reboot is slow, but certain.

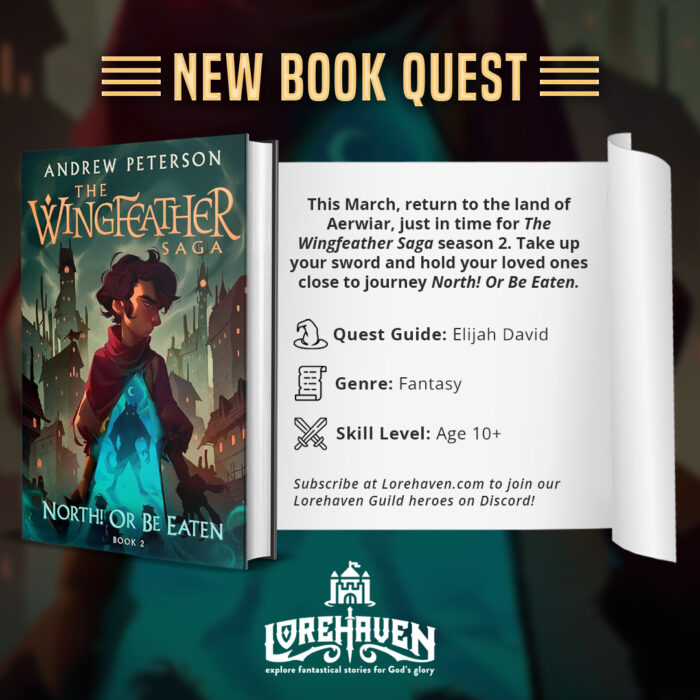

Where Christian fiction survives, it’s experimenting. Authors are testing waters. So are publishers.

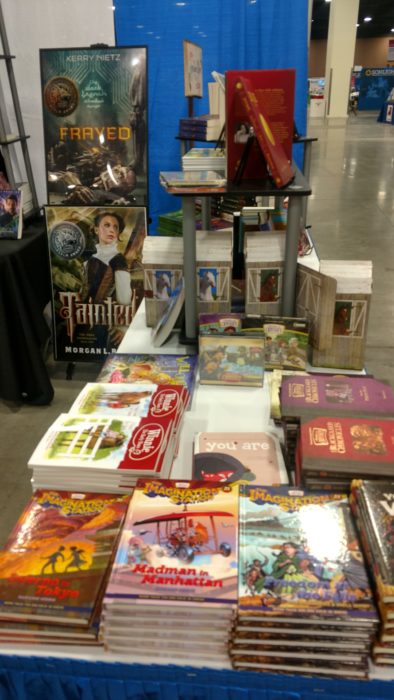

Indie vendors, like the Realm Makers Bookstore, are taking fantastical-genre books directly to new fans.

The stories are improving. They’re going places other stories, including secular YA fantasy, simply can’t go.

Especially if those other stories end up getting stuck in YA Twitter Hell. Or limited to particular authors, who manage to land perfectly at the exact intersectional vertices that are trending that month. Or focused exclusively on whatever sexual weirdness happens to be poking all the “right” hashtags.

If there’s anything fantasy fans should know, it’s that amazing things can happen. Time can bend back on itself. You can find alternate worlds in the weirdest places. Not the expected places.

Based on this, my prediction is crazily simple. I say those future fantastic worlds will best be found in future-Christian bookstores, and future Christian-labeled novels.

And I can’t wait to share these future-generation stories with my grandchildren.

- I often use fantasy as a catch-all term to describe fantasy, science fiction, paranormal, horror, magic realism, steampunk, and any fantastical genre. ↩

- As a few readers have pointed out, it appears ebook sales are mostly slacking if they’re released by traditional publishers. Many independent authors say their ebooks are still doing very well. ↩

This article has a few faulty assumptions.

1. Ebooks are dying. They are only dying for traditional publishers, who often price them higher than the paperbacks. In the indie realm, where they’re not tracked, they’re still going great guns. The death of ebooks has been greatly exaggerated. Pay attention to your sources.

2. The YA Twitter audience has nothing to do with the Christian writing circle. If those people are your audience, fine, go in with your eyes open. But most Christians are writing for the homeschool YA audience. If the YA Twitter SJWs dogpile your book, laugh at them. All they’re doing is giving you free publicity. They likely won’t even know your book exists.

Kessie, my main points are that (1) print is still popular, so its demise has been exaggerated; (2) YA Twitter is a factor for authors who want to skip the “Christian label,” which incentivizes growth in the very market (that is, “Christian fiction” so clearly labeled) that you and I both mentioned. 🙂